Held Up By History: Roman Ruins Provide Building Blocks For Serbian Village

Amid the devastation after World War I, Verica Ivanovic's grandfather used whatever construction materials he could find to build the family's home including, unbeknown to him, bricks from the Roman Empire.

The house and its ancient foundation are still used by the family in central Serbia's Stari Kostolac -- on the outskirts of what was once a major Roman settlement and military garrison then known as Viminacium.

It was only years later that the family realised the bricks were cobbled together from the ruins belonging to structures from the once powerful empire.

Emilija Nikolic, a research associate from the Belgrade Institute of Archaeology, estimates that the bricks found on Ivanovic's house likely originate from the third or fourth century AD.

"It's kind of awkward, I know it's Roman. But everyone was doing it," Ivanovic, 82, told AFP.

The fields around Viminacium remain an archaeological gold mine teeming with ancient coins, jewellery, and other artefacts.

In an abandoned backyard near Ivanovic's home lies the remnants of an ancient Roman wall.

"We were ploughing potatoes in a field. I looked down and saw a cameo... When I turned it with my hoe, I saw a beautiful female face," said Ivanovic. "It's in a museum now."

For centuries, residents near Stari Kostolac have used the bricks and mosaic tiles and other pieces from antiquity that were found in abundance in the area to fill everyday needs.

"Historians in the 19th century noted that a peasant from a nearby village used a sarcophagus as a pig feeder," Nikolic told AFP.

Today, the sarcophagus -- which features images from the ancient Greek myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece -- resides in a museum.

According to archaeologists, Viminacium was once the provincial capital of Rome's Moesia region and supported a population of about 30,000 inhabitants during its heyday.

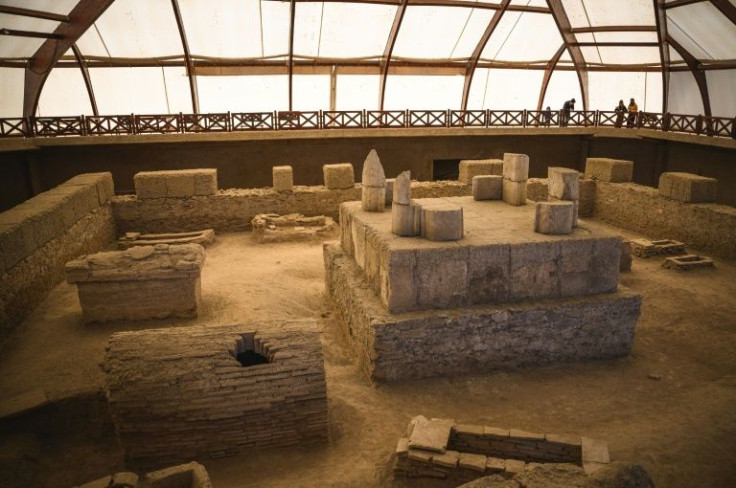

Tens of thousands of artefacts have been unearthed from the area so far, including a Roman bath with heated floors and walls, a fleet of ships, and hundreds of sculptures.

The ancient city is also believed to have been home to one of the largest necropolises discovered in territory belonging to the former Roman empire, with about 14,000 tombs unearthed.

Viminacium started to decline following the Hun invasion in the mid-fifth century AD and was completely abandoned by the time Slavs arrived in the region at the beginning of the seventh century.

The archaeological site is also the only major Roman settlement that has no modern city built on top of it, according to experts.

"You can't see Londinium anymore because modern London is there. No Lutetia nor Singidunum -- Paris and Belgrade are built on top of it," said Miomir Korac, director of the Belgrade Institute of Archaeology.

Sprawling underneath Stari Kostolac's corn fields are the remnants of the entire ancient city -- including temples, an amphitheatre, a hippodrome, a mint and an imperial palace, according to extensive scannings, Korac said.

Just two to three percent of the area has been excavated and explored by experts to date.

But centuries after its fall, the ancient garrison city is under siege again.

For more than four decades, nearby mining projects, including the recent expansion of a coal project and a power plant, have increasingly encroached into the area.

"It has definitely put (the site) in danger, as many ancient buildings have already been destroyed by building the mine," Nikolic said. "We have saved what we could."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.