Duterte Couldn't Fix Philippines' Food Inflation Problem – Can Marcos Do It?

Food inflation is a problem worldwide. But it is more of a serious problem in low-income countries like the Philippines, which relies on food imports to feed its population and where food spending counts for close to 50% of the family budget. In addition, the weakening of the Philippine currency against the dollar since the Federal Reserve began hiking interest rates has worsened matters.

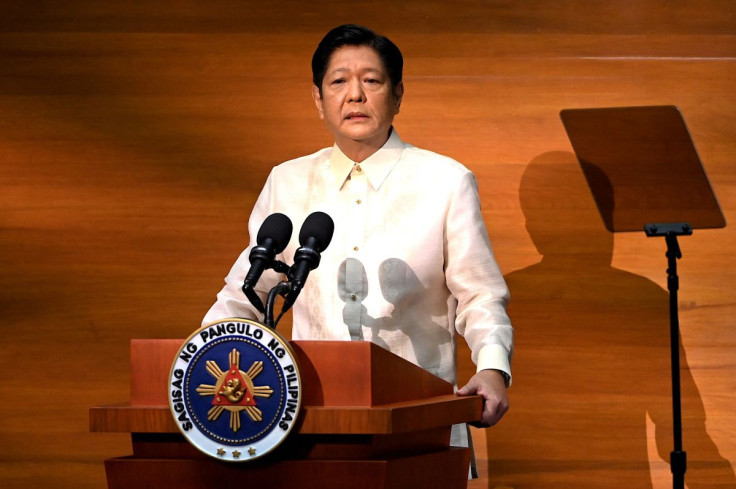

The problem became so severe last spring that it prompted the newly elected president Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to appoint himself as agriculture secretary in hopes of bringing food costs under control.

But that wouldn't be easy, as he would have a few options in the short-term to change the imbalance between demand and supply, according to an article published by the International Endowment for Peace in July.

"The Philippines is the most food-insecure country in emerging Asia due to its reliance on imported food to feed its expanding population," Trinh Nguyen, a nonresident scholar in the Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the author of the article, wrote.

Moreover, she thinks that Marcos' self-appointment is a worrisome sign of his country's food self-sufficiency amid a looming crisis.

Aédán Mordecai, an intelligence analyst at Sibylline who focuses on the Asia Pacific region, agrees, providing further insight into the Philippines' food insecurity problem.

"While the Philippines is not the only country in the region to be experiencing a depreciating currency, the Philippines is reliant on imports to a greater degree than some of its ASEAN peers," he told International Business Times in an email. "And that raises costs significantly for both households and companies."

Manila is highly dependent on imports for essential oil and coal supplies to meet domestic demand. In addition, it relies on imports for vital agricultural and food products such as fertilizer, soybean (used for animal feed in livestock farming), rice (with the country the second biggest importer in the world), salt and wheat.

Mordecai also thinks that president Marcos has a few immediate options. One of them is food subsidies, but that would be just a "band-aid" — to use Nguyen's terminology — which will deteriorate the country's fiscal situation. And that would plunge the Philippine peso further against foreign currencies, throwing the country into a vicious cycle of peso depreciation-higher food prices.

Another option is to let the nation's central bank raise interest to support the peso, but that could hurt the country's economic growth and employment situation and eventually hurt the currency, as slower economic growth will fuel expectations for a lower peso.

Then there's a long-run option, which could eventually solve the problem for good: boost domestic capacity for food production (which worsened under President Rodrigo Duterte) and diversify its energy sources to prevent such issues from arising again.

Nguyen is on the same page. "Stopping the peso's slide is still within the central bank's mandate, and improving food production to reduce exposure to volatile global prices will be key to feeding his country's rapidly growing population," she wrote.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.